Scone

She made scone all the time, butonly measured ingredients when forced to, only wrote down the recipe at someone’s behest.

Read MoreThis essay was written collaboratively by the editors of Dead Housekeeping. We honor how caretakers come together across race, religion, and nationality to mourn, to commiserate, and to plan after cataclysmic events. We owe the idea to our founding editor Lisa Schamess, for calling us in as a group to write this about the letter-writing, stamp-licking coffee klatsches of the 1960s and 1970s. It was healing for us to write after the U.S. election results last week. We hope it’s healing to read as well.

How to Make the Coffee

First, go to the store. In addition to things for the coffee, make sure and buy tissues. Some people will need a place to cry tonight.

The house may sparkle or it may be filthy. Maybe you clean when you are upset, maybe your nervous energy propels you to scrub the baseboards, or maybe the house has gone all to hell. If a mountain of junk has grown on the table, clear it off. You can put everything neatly in its place, or throw it in a hamper for later. You'll need a clear workspace, a place for everyone's cups.

Bring up the folding chairs. Alter the furniture for company and tasks. Vignettes for conversation, for work, for sitting next to.

Look for the folding table you last used at Thanksgiving. It isn't in the basement. Did you lend it to Sybil and forget to get it back? Or did the leg break? No matter. Someone has one you can borrow. Start with Sybil.

Consider making coffee cake: That recipe that everyone raves over. A little sweetness at a time like this is always welcome.

At least one person you invited doesn't drink coffee. Check your tea supply.

Not everyone will want what's in that cup. Offer anything. Everything. Until you get it right.

The coffee is bitter and the product of so many hands.

The milk is farmed from beings who made it for their children, not ours.

The sugar is bitterest of all, bitterest of all.

How do we raise our bitter cups together?

Let the children play under the table. What do they know yet. What will they know.

Drink the bitterness, leave lipstick on the cup.

You have a close friend who comes early to help set up. She's telling you what she cannot say later. She thoughtfully sets a napkin under the percolator spout.

This is just your "little coffee klatsch" you tell the men. You'll be home by 11 or so.

Light a candle in the bathroom. Not everyone wants to cry in public, but those who need privacy deserve warmth, too.

There's the smell of coffee, perfumes, and store-bought pastries. Cocktail napkins, condiments, cups stacked on a tray.

It will feel good to see everyone together. Your heavy hearts will fill the whole room. Everyone brings what they can. For example: There's nothing wrong with a friend liberating a pack of legal pads and two boxes of envelopes from the office where she works. We all find our way to stock the communal tote bag of supplies.

An envelope on an end table is displayed quietly for group costs. One friend leaves a generous ten every meeting. It's what she has to offer.

The dryer will buzz. Leave it.

Draw water. Fill the urn to the line. Put the basket into the urn and turn the stem. You will know it is set right when you feel the click in the notch.

Measure out the grounds, spoon by spoon. Add one for the pot.

Put the lid on and turn it to lock. Plug in the cord. The brew will begin to bubble.

Let your children watch all this.

Someday they too will mix and brew and stir the pot.

Call them from under the table to put the pastry on the plate, the good one with gold leaf that your grandmother gave your mother. Let them lick their fingers and put them back into the pastry box. Pretend not to see. A little spit never killed a soul.

One day when you re old, write the instructions for the percolator on an index card, and tape it to the inside of the box the percolator came in. Your children will need this when you're gone, when percolators have fallen out of common use and yet await their time for gatherings.

- The Housekeepers

Do your best. Encourage others. When young men ask you for money, offer them odd jobs. Some of them will grow up to look in on you and your wife when you are old.

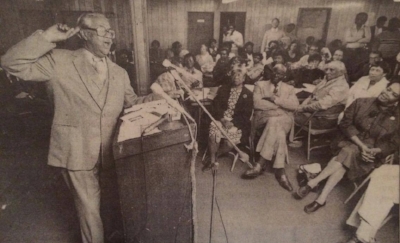

The author's grandfather, Dr. Jack Brooks addresses an audience after a 1986 civil rights march via Fort Worth Star-Telegram Archives.

Open a clinic with your brother and treat everyone, regardless of their ability to pay. When your patients need to be hospitalized, refuse to treat them in the hospital’s basement. Black patients deserve to be treated like everyone else.

Tell your granddaughter she can be anything she wants. This is not the prevailing thinking in 1970, but you don't care about that. Equality is equality.

Accept the nomination to be the first Black member of the Parks Commission. Insist that the sign identifying a deep red rose as “Niggerboy” be removed before your family walks past it when you are sworn in. Casual racism is still racism.

Vote. Volunteer. Take your children with you. Teach them that not voting is never an option. Your daughter will remember this when George Wallace is on the ballot in 1980. Your granddaughter will remember when she votes with her 8-week-old son in 1996. Your great-grandson will rail against not voting in 2016.

The politicians need you. They will realize, on the morning of the Chamber of Commerce breakfast for President Kennedy, that there are no Black people in the audience. When they call to invite you and your wife, tell them that two tickets are not enough. Ask for 50. They need you. They will give you 50 tickets.

They need you. Ask for your 50 tickets.

My grandmother balanced her checkbook on Sundays, after Johnny Carson had gone off the air. I’d stay up late with her, listening to the CLICK CLICK CLICK of the adding machine as we watched reruns of Hitchcock muted on the screen.

“You must take care of your finances, Franny,” grandma would say as she checked off each deposit and withdrawal, all written in her elegant parochial school handwriting. “I have a perfect credit score. Never been late on paying, not even once!”

She’d say that last bit smugly, before turning back to her calculations. Occasionally I’d hear her muttering tidbits of advice while she tried to reconcile the bank’s statement with her own precise records.

Next to the adding machine, grandma kept a neatly folded, damp paper towel, so she could carefully wipe each finger each time they grazed the black carbon copy paper.

“Always make a copy when you write a check. And use ink,” she’d say. “Most folks are decent, but that’s no excuse for being an easy mark.”

She was full of this unsolicited advice.

“Never finance toys, Franny. You take a loan for a house, even a car. Sure. But never toys. No one needs a record player enough to go into debt for it. “

Grandma survived as an orphan during the great depression. That kind of wasteful indulgence “got her dander up,” as she would say.

“Balancing a checkbook is easy. Money in, money out, easy as pie. It’s getting the money that’s the hard part. “ This was a constant refrain.

“You have to work hard. Nothing is free.”

- Frances Locke is a writer from New York City and the founding editor of Witty Bitches Magazine. She’s currently living a self-imposed exile in Las Vegas, with her partner and children, and enjoys proselytizing about the wonders of cats whenever possible. You can find her on Twitter at @frances_locke

It is strict adherence to ritual that keeps your loved ones safe. Rise at 4 am to pray. The Gods are most attentive in the early hours. Morning prayers, an oil lamp lit every evening before the electric lights are flicked on, a ban on Friday travels, these are your lines of defence against evil.

Be watchful, ever vigilant for the intrusion of errant spirits into the family. A crying child in the evening, a sure sign of the Evil Eye.

Gather your arsenal while muttering under your breath about the visiting neighbour-woman, with her too abundant praises, her too ardent admiration of beauty and intelligence in the child. Steel yourself, this is no trifling issue. Shut your ears, your heart to the child’s sobs, she is held and comforted by her mother.

Work quickly, ignoring the arthritis gathering in your joints. Before misfortune falls.

First the dried red chillies, one, two.

Then the black mustard seeds. A small pinch will do.

Gather together with grains of rice,

Circle the child’s head precisely thrice.

Throw the spices with deadly aim

Into the fire of licking flames.

Chanted prayers allay the fears,

And distract the young one, now no longer in tears.

image by Asha Rajan

Keep a keen eye for the wisps of smoke rising from the fire-flung spices. These mark the demise of the Evil Eye, the restoration of the world to its rightful order.

Your daughters, and one day your granddaughters too will repeat these actions, and think of you.

"Hammer Cuddle," by Tiffa Day, via Flickr

1. Maybe it’s Hollywood, 1930’s. Pepper trees line the boulevards. Down Vine, my grandmother makes almond cake for what they call entertaining. She can’t get used to her new life. My grandfather lines up cigarettes in ashtrays around his typewriter, two or three burning at a time. Bob Hope calls. The clacking sounds to her like machine guns through the stucco. Sometimes, there is a bang. Start with a three layer yellow cake, whatever you’re used to, or just make it from a box like she did. Sometimes, nothing comes through the wall but silence.

2. Cook ¼ tsp instant coffee, sugar, corn syrup, water, and almonds in a small saucepan until it reaches hard crack stage. 290 degrees. Add soda, for fizz. The spines of her cookbooks line up against the milky tilework. Betty Crocker holds a cake up, hair backlit. In the pale kitchen, Grandma is nineteen—her hair is like a movie starlet’s, waved and shellacked—a gardenia behind one ear. Her waist no larger than two hands, white crinoline flouncing around her knees. When she needs to reduce, the doctor gives her pills.

3. Pour onto an ungreased pan, bare and cold. The mixture will grow brittle as it cools. Layer the cake with whipped cream. Grandma will tell us over and over again about schmaltz and gribenes too, but she will never describe how to make them. Too heavy, she will say, and anyway she hasn’t eaten that way since she was a child. There are no kosher butchers at Ralph’s on Santa Monica. Wrap a hammer in a towel and crush the candy into shards. Press them into the top and sides. She displays the cake, elegant and brown, on a white pedestal.

4. The beautiful part is you can freeze your cake ahead. It will slowly thaw under the icing until tender and light, ready for company. Food is more wholesome this way. No one plucks a chicken like they did among the tenements, blood drained, the meat blessed and waiting.

- Nora Brooks is a writer whose poetry, fiction and cultural coverage has appeared in PopMatters, H.O.W. Journal, Alimentum, Monkeybicycle, The Best American Poetry blog, and elsewhere. A recent graduate of The New School, her short prose chapbook How to Boil an Egg and Other Recipes was this year's runner-up in the prose contest of George Mason University's Gazing Grain Press, and a mini-chapbook will be published in 2015. She lives in Portland, Oregon with her husband and too much taxidermy.