How to Make the Coffee

This essay was written collaboratively by the editors of Dead Housekeeping. We honor how caretakers come together across race, religion, and nationality to mourn, to commiserate, and to plan after cataclysmic events. We owe the idea to our founding editor Lisa Schamess, for calling us in as a group to write this about the letter-writing, stamp-licking coffee klatsches of the 1960s and 1970s. It was healing for us to write after the U.S. election results last week. We hope it’s healing to read as well.

How to Make the Coffee

First, go to the store. In addition to things for the coffee, make sure and buy tissues. Some people will need a place to cry tonight.

The house may sparkle or it may be filthy. Maybe you clean when you are upset, maybe your nervous energy propels you to scrub the baseboards, or maybe the house has gone all to hell. If a mountain of junk has grown on the table, clear it off. You can put everything neatly in its place, or throw it in a hamper for later. You'll need a clear workspace, a place for everyone's cups.

Bring up the folding chairs. Alter the furniture for company and tasks. Vignettes for conversation, for work, for sitting next to.

Look for the folding table you last used at Thanksgiving. It isn't in the basement. Did you lend it to Sybil and forget to get it back? Or did the leg break? No matter. Someone has one you can borrow. Start with Sybil.

Consider making coffee cake: That recipe that everyone raves over. A little sweetness at a time like this is always welcome.

At least one person you invited doesn't drink coffee. Check your tea supply.

Not everyone will want what's in that cup. Offer anything. Everything. Until you get it right.

The coffee is bitter and the product of so many hands.

The milk is farmed from beings who made it for their children, not ours.

The sugar is bitterest of all, bitterest of all.

How do we raise our bitter cups together?

Let the children play under the table. What do they know yet. What will they know.

Drink the bitterness, leave lipstick on the cup.

You have a close friend who comes early to help set up. She's telling you what she cannot say later. She thoughtfully sets a napkin under the percolator spout.

This is just your "little coffee klatsch" you tell the men. You'll be home by 11 or so.

Light a candle in the bathroom. Not everyone wants to cry in public, but those who need privacy deserve warmth, too.

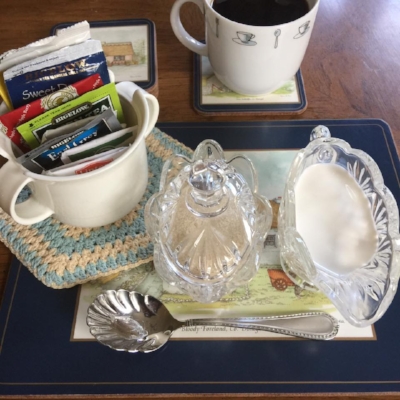

There's the smell of coffee, perfumes, and store-bought pastries. Cocktail napkins, condiments, cups stacked on a tray.

It will feel good to see everyone together. Your heavy hearts will fill the whole room. Everyone brings what they can. For example: There's nothing wrong with a friend liberating a pack of legal pads and two boxes of envelopes from the office where she works. We all find our way to stock the communal tote bag of supplies.

An envelope on an end table is displayed quietly for group costs. One friend leaves a generous ten every meeting. It's what she has to offer.

The dryer will buzz. Leave it.

Draw water. Fill the urn to the line. Put the basket into the urn and turn the stem. You will know it is set right when you feel the click in the notch.

Measure out the grounds, spoon by spoon. Add one for the pot.

Put the lid on and turn it to lock. Plug in the cord. The brew will begin to bubble.

Let your children watch all this.

Someday they too will mix and brew and stir the pot.

Call them from under the table to put the pastry on the plate, the good one with gold leaf that your grandmother gave your mother. Let them lick their fingers and put them back into the pastry box. Pretend not to see. A little spit never killed a soul.

One day when you re old, write the instructions for the percolator on an index card, and tape it to the inside of the box the percolator came in. Your children will need this when you're gone, when percolators have fallen out of common use and yet await their time for gatherings.

- The Housekeepers